“How Do They Learn Math?” Learner-Centered Mindsets and Strategies of Mastering Math

By Dr. Caleb Collier, Trey Lackey, and Dr. Tyler Thigpen

Dr. Caleb Collier is Director of The Institute for Self-Directed Learning and co-founder of The Forest School: An Acton Academy.

Trey Lackey is Guide and Math Specialist at The Forest School: An Acton Academy and Research Assistant at The Institute for Self-Directed Learning.

Dr. Tyler Thigpen is CEO of The Forest School: An Acton Academy and Institute for Self Directed Learning in Trilith south of Atlanta, and Academic Director at the University of Pennsylvania Graduate School of Education.

Glimpse at a “Math Lab” at The Forest School: An Acton Academy

OVERVIEW

“How do they learn math?”

That might be the most common question we get asked at The Forest School: An Acton Academy and The Forest School Online. In self-directed learning environments like ours, young people shoulder the responsibility of their education and build the skills they need so that they can learn anything. Including math.

But how does it work?

To more fully appreciate the answer(s) to this question, The Institute for Self-Directed Learning engaged with learners to better understand their journey to math mastery. This report summarizes the learnings that surfaced as we collaborated with young people to research how they learn math in a self-directed environment.

There are a variety of stakeholders interested in understanding if and how young people develop math mastery in a self-directed environment, including teachers and parents who have their doubts, school leaders who worry how this pedagogical approach impacts academic performance, and students who may be skeptical they can “own” their math learning. This report seeks to address all of those groups.

The headline? The study finds that when young people cultivate a sense of relevance, resourcefulness, and persistence—and combine these mindsets with strategies like leveraging diverse resources, breaking down problems, and setting clear goals—they effectively master math in a self-directed learning environment.

Research Design and Methodology

Purpose of the study: Analyze the approach to learning math at The Forest School, looking for 1.) strategies we can glean and share from learners who have mastered math concepts, and 2.) improvements we can make in our supports for math learning.

Participants: Learners (grades 4-12) who either demonstrated grade-level mastery or above on a diagnostic test (the IXL real time diagnostic) or had scored 530+ on SAT Math or 22+ on ACT Math. These milestones (530+ SAT Math, 22+ ACT Math) were chosen because they are above the most recent national averages for the Class of 2023—508 for SAT Math and 19.0 for ACT Math. We interviewed 24 learners (46% learners of color; 29% on scholarship).

Data collection: We conducted one-on-one interviews with participants, gathered survey responses, and pulled data from e-learning platforms (primarily focused on categories of time spent and progress made as measured by the platforms). See the Appendix for interview and survey questions.

Data analysis: We analyzed the interview transcriptions, survey responses, and e-platform data using thematic analysis. The findings were then distilled into mindsets (beliefs learners have about themselves and their abilities) and strategies (concrete actions they take) to learn math in a self-directed environment.

Study limitations: This study has three key limitations. First, participants were selected based on demonstrated math mastery (530+ SAT Math, 22+ ACT Math, or grade-level proficiency on IXL), excluding those who struggle with math and limiting insight into diverse learning paths. Second, findings are based on The Forest School’s unique model and may not generalize to other educational settings with different structures and resources. Lastly, the study relies on qualitative data from interviews and surveys, which, while insightful, introduce subjectivity. Future research could include broader learner samples and quantitative tracking for deeper validation.

Schoolwide goals for and approach to math learning: Graduates are expected to at a minimum demonstrate mastery through Algebra 1 and Probability & Statistics. Guidance for learners is to spend at least forty-five minutes everyday on math learning. The Forest School: An Acton Academy and The Forest School Online value both conceptual and procedural math learning, offering dedicated human and material resources to support both approaches. Both schools embrace a blended math pedagogy that combines self-directed learning on e-learning platforms like Khan Academy, Zearn, and IXL, peer-to-peer learning, and biweekly adult-led, inquiry-based instruction known as Math Labs.

Past Research

Research on learner-centered math instruction presents a mixed picture—while student-driven approaches can foster deeper understanding, critical thinking, and engagement, studies also highlight challenges such as gaps in foundational knowledge, limited guidance, and difficulties with self-regulation.

Opportunities of Learner-Centered Math Learning

Research on Open and Reform Mathematics Classrooms

Key Work: Boaler, J. (2002). Experiencing School Mathematics: Traditional and Reform Approaches to Teaching and Their Impact on Student Learning.

Contribution: This work contrasts traditional, teacher‐centered methods with learner‐centered, open approaches. Boaler’s research shows that when students engage in open-ended problems, collaborate, and make personal connections to math, they develop deeper conceptual understanding and increased confidence.

Cognitively Guided Instruction (CGI) Research

Key Work: Carpenter, T. P., Fennema, E., Franke, M. L., Levi, L., & Empson, S. B. (1999). Cognitively Guided Instruction: A Knowledge Base for Reform in Primary Mathematics Instruction.

Contribution: This body of work emphasizes understanding how children naturally think about and solve math problems. By centering instruction on students’ problem-solving processes rather than rote procedures, CGI supports a learner‐centered approach that builds deep mathematical understanding and promotes flexible thinking.

Mathematical Thinking and Problem Solving

Key Work: Schoenfeld, A. H. (1992). Learning to Think Mathematically: Problem Solving, Metacognition, and Sense-Making in Mathematics.

Contribution: Schoenfeld’s research underscores the importance of metacognition, problem-solving strategies, and active engagement with math. His work has been influential in designing instructional approaches that promote self-directed, reflective, and resilient math learners.

Challenges of Learner-Centered Math Learning

Lack of Structure Leading to Gaps in Foundational Skills

Key Work: Kirschner, P. A., Sweller, J., & Clark, R. E. (2006). Why Minimal Guidance During Instruction Does Not Work. Educational Psychologist, 41(2), 75–86.

Contribution: This study argues that unguided, discovery-based learning—common in learner-centered models—can lead to gaps in foundational math skills. The research finds that students who receive minimal instructional guidance often struggle with misconceptions, disorganized knowledge, and inefficient learning, making it harder for them to build a solid math foundation. The authors conclude that while exploration has value, fully unguided learning is less effective and efficient than structured instruction, particularly for novice learners.

Limited Guidance and Resources Impacting Student Progress

Key Work: Boatman, A. (2012). Evaluating Institutional Efforts to Streamline Degree Completion: The Causal Effect of Modularized Developmental Math. Vanderbilt University.

Contribution: This study examines the shift to self-paced, modular math courses at the college level, finding that students with reduced instructor support were less likely to persist and succeed in math. Without clear structure and guidance, many students struggled to navigate course content, leading to lower completion rates and stalled progress. The findings suggest that while self-directed math models offer flexibility, insufficient support and resources can prevent students from advancing effectively.

Student Motivation and Self-Regulation in Self-Directed Learning

Key Work: Pokhrel, M., & Sharma, L. (2024). Investigating Students’ Perceptions of Self-Directed Learning in Mathematics at the Basic School Level. Journal of Mathematics and Science Teacher, 4(3), em066.

Contribution: This study surveyed middle school students on their attitudes toward self-directed math learning and found that many lacked confidence in self-regulation and motivation. Students expressed difficulty managing their own learning, tracking progress, and staying engaged without external structure. The study highlights the importance of explicitly teaching self-regulation strategies, as low motivation and poor self-monitoring can hinder success in learner-centered math environments.

Ultimately, the effectiveness of learner-centered math education depends on striking the right balance between autonomy and support, ensuring that students benefit from active problem-solving and conceptual reasoning while also receiving the structure and guidance necessary for long-term success.

Our Contribution

Our study aims to contribute to this field of inquiry by:

Linking Mindsets with Strategies: It documents how specific attitudes—like seeing math as both inherently and instrumentally relevant—combine with concrete strategies (e.g., resource utilization, problem breakdown, and pivoting when challenged) to foster math mastery in self-directed environments, a pairing not extensively detailed in prior research.

Highlighting Learner Agency and Resourcefulness: It provides new evidence that learners in a self-directed setting actively construct their own math learning journeys by leveraging multiple supports—digital tools, peer interactions, and educator guidance—which underscores the importance of designing environments that nurture resourcefulness and persistence.

Emphasizing Relevance in Multiple Dimensions: The study uniquely distinguishes between math’s inherent value (learning for the joy of discovery and deep understanding, as seen in fields like engineering) and its instrumental value (serving as a pathway to college and career readiness), demonstrating that integrating both dimensions is crucial for sustaining student motivation and success.

This study adds nuance by showing that math learning in learner-centered environments is not just about acquiring content but about developing a holistic set of mindsets and strategies that empower learners to own and persist in their math education.

THE BIG IDEA IN BRIEF

Before we do a deep-dive into the findings, here is a brief summary of what we found:

Mindsets for Success

See the Relevance:

Inherent Value: Math provides essential tools for creative fields like engineering.

Instrumental Value: Math builds critical thinking needed for college and careers.

Both connections are powerful; missing one can hinder motivation.

Embrace Challenge:

Focus on mastering concepts rather than just getting answers.

Accept mistakes as part of the learning process and use them to improve.

Leverage Community:

Recognize that you’re not alone—learn from peers and guides.

See educators as coaches and technology as helpful assistants.

Strategies to Deepen Learning

Use Available Resources:

Attend Math Office Hours and Math Labs.

Utilize digital tools, e-learning platforms, and online videos.

Work with peers in study groups to share insights and support each other.

Break It Down:

Think through problems in your head first, then write them out.

Use trial and error to explore different solutions.

Seek different perspectives when stuck and always check your work.

Take Action:

Set clear, personal goals and make a daily plan for math study.

Prioritize math and make dedicated time to work on it.

If you hit a wall, take a break, pivot your approach, and try again.

Key Reminders for Educators and Parents

Cultivate curiosity and help students see math’s relevance to their interests and futures.

Celebrate effort and progress, praising the process of learning.

Create spaces for collaborative problem-solving and resource sharing.

Encourage self-directed learning by letting students choose how and when to learn.

By blending these mindsets and strategies, we empower every learner to own their math journey, overcome challenges, and build a deep, lasting understanding of math.

FINDINGS

Part 1: Mindsets

In analyzing the data, here are the most useful mindsets learners identified that help us answer the question “How do they learn math?”

The Work is Relevant

Most learners expressed through the surveys and interviews that they saw a clear connection between learning math and their own interests. We identified three prevalent themes:

Relevant to Future Goals

Relevant to Current Interests

Relevance by Necessity

Let’s walk through these themes one at a time.

Relevant to Future Goals

Most references of the relevance of learning math tended to be future-oriented (connected to college or career). Here’s a quote from one of the learners:

“At first, it can be hard to see how learning complicated math will directly benefit my future. However, since I plan to attend college, I understand that math is essential in many fields and careers. Whether it's for data analysis, budgeting, or just problem-solving skills. I've grown to learn that math provides tools that many people can use in real-world situations. Even if I don’t end up using advanced math directly in my career, you are still improving your critical and analytical thinking which can benefit you very much in the future.”

And another:

“Yes. I want to be an engineer; learning and mastering math concepts is absolutely necessary for any engineering field. An example in aerospace (the field I want to go into) could be using formulas to design airfoils that can properly lift a vehicle.”

One learner said they didn’t see a connection between math and their own interests and life goals because they wanted to be a professional soccer player. Others said that learning math was necessary to get into college, but probably wouldn’t be applicable to their career fields. An interesting finding in the interviews: elementary learners were just as likely as high school learners to discuss college/career goals in relation to their math learning.

Relevant to Current Interests

For some learners, though, learning math wasn’t just tied to their future goals—it was connected to their present interests. Learners that see alignment between math and their current interests either see it applicable in their hobbies (coding, robotics, architecture), or they expressed a deep curiosity to learn math for the sake of learning math. “I want to know everything there is to know about math…that’s what motivates me,” one elementary learner said. “I just want to do my best in everything,” another said. “That’s what keeps me going.”

Relevance by Necessity

Another sentiment that arose from the conversations and survey data was a simple pragmatism: learning math is just something I have to do. Many learners mentioned that they were neither excited or overwhelmed by math—it was just part of their learning plan and they needed to master the basics to move on to the next level. Their “desire” to learn math was practical. One middle school learner said that, when they set daily goals, they “prioritize math and get it done first” because “it feels good to check it off of [their] to-do list.”

Learners see math as relevant when it provides essential tools for fields like engineering and supports future goals like college and career success. Both inherent and instrumental values work together to drive motivation. Without either connection, learners can struggle to appreciate math's importance.

Why It Matters

In prior research, we outlined the Pathway of Self-Directed Learning. There’s a general course most people take as they take on ownership of their education. The first phase of this pathway is developing a “desire to learn.” Before an individual can set out to master a concept on their own, they must want to learn it. That’s the starting place, the spark that pushes the learning journey forward. If learners don’t see clear relevance in the learning, they will never build the “desire to learn” in the first place.

What Can Be Done?

Most math curriculum that has been and is being developed focuses on what students are learning (content) and ignores why (relevance). Below are some ways to help young people find relevance in their learning

What Parents/Caregivers Can Do:

Cultivate curiosity. Give young people time, resources, and encouragement to follow their interests, both in and out of school settings.

Celebrate a growth mindset. Praise the process and the effort, not the product. Especially in math learning, reframing an attitude of “I don’t get it!” to “I don’t get it…yet” can be powerful.

Allow for productive struggle. Learning something new can be hard! Don’t step in to “rescue” young people before they’ve had a chance to persist through a challenge on their own.

What Educators Can Do:

All of the above in the “Parents/Caregivers” section!

Design learning across disciplines. Give learners practice using math, logic, and problem solving skills in authentic scenarios. In these cases, learners aren’t searching for relevance and asking “why am I learning math?” Instead, they’re asking “how can I use what math I know to address this real world problem?”

Encourage young people to step back and see the big picture. Learning math requires mastering fundamental skills, then moving on to more complex concepts. Math is a journey, not a destination. Helping learners reflect on their growth and visualize where they’re going next helps them see the relevance of what they are learning now.

What Learners Can Do:

Start with the end in mind. Who do you want to be and what do you want to explore when you graduate? That may involve going to college, going into a career, starting a business or non-profit, taking a gap year, or joining the military. How does that goal for the future impact what you’re doing now?

Stay curious. Math learning rewards curiosity. Lean into the challenge of learning math for the sake of learning math! Becoming an agile problem solver and critical thinker will prepare you well for whatever you want to explore in life.

Resources Are Abundant

One thing that stood out from the data: learners that have demonstrated math mastery see a variety of resources at their disposal. These resources can be people (educators, peers, siblings), materials (white boards, notebooks, manipulatives), technology (AI, YouTube, e-learning platforms), or school supports (Math Labs and Office Hours). We’ll dive into how these resources are utilized later in the strategies section. First, though, it’s important to highlight the attitudes and beliefs learners have about how to make use of the resources available to them.

I’m Not on My Own

Even though learners have taken responsibility for their own learning, they do not see themselves as isolated in the learning project. “Everyone is in the same boat,” one learner said, “and, like they'll try and find someone who is ahead of them and their [math e-learning] platform so that they can be like, oh, you've done this, can you help me with it?” In school, learners see themselves as part of a larger whole. Some of their peers are further along and can be a resource to go to. Some of their peers are currently learning the same material and can be a thought partner. Other peers are working on concepts these learners have already mastered, providing an opportunity for mentorship. The prevailing theme is: we’re in this together; I’m not alone. “I get to see the way other people do math,” one learner said, noting that it enhanced their own learning. “We are all trying to learn together, and we all think differently,” said another, “which means we can contribute different parts of the problem to find the solution.” Elementary learners tended to more frequently cite seeking support from older peers or adults than high school learners.

Adults Are Guides

In a learner-centered environment, educators are often called guides, coaches, or facilitators. More than just a change of terms, these new labels highlight a re-imagining of the role of the adult in the room. In traditional schools, “teachers” are content experts. A math teacher possesses math knowledge, and passes that knowledge on (via direct instruction) to students. In learner-led spaces, resources are abundant and educators are one of many supports learners can turn to. By serving in the role of “guide” instead of content expert, educators are able to personalize support and help each learner identify and utilize the resources that work best for them.

Technology is an Assistant

In survey responses, participants identified their top three resources as online searches (Google, YouTube, etc.), e-learning platforms (Khan Academy, Zearn, IXL), and AI chatbots (ChatGPT, Khanmigo, Gemini, etc.). Digital tools have become a “go to” for this generation, especially when it comes to math learning. We’ll explore how they are using these tools later in the report, but the mindset underlying these integrations of technology is important to name: learners see a world of resources at their fingertips that can assist them in learning anything. No matter the challenge level, participants felt confident they could find tips, how-to’s, breakdowns, and practice through a variety of digital sources. On the flip side of the digital coin, technology could be a “crutch” for deep learning, allowing learners to “offload” the hard work of problem solving to AI chat bots or “gaming” e-platforms by clicking through problems without engaging in the work. Learners we interviewed were quick to point out that how they use technology (as a means for deep learning) is more important than access to the digital tools themselves.

What It Matters

Phase Two of the Pathway of Self-Directed Learning is “learner resourcefulness.” Once the desire is there and a young person wants to learn (Phase One), they start gathering resources. Learners that lack awareness of what supports are at their disposal or lack confidence in using those supports will have a more difficult time starting their learning journey and persevering when challenges arise. When we asked young people what helped them master math on their own, they were quick to name the resources they utilized.

What Can Be Done?

A key shift in moving from traditional schooling to self-directed learning is the way resources are deployed. Traditional classrooms tend to center curriculum (content) and teachers (instruction). Learner-led classrooms center inquiry (“How can I do this? Where can I find out?”), collaboration (“Who can help me?”), and experimentation (“What else can I try?”). Below are some recommendations for building this mindset of resourcefulness

What Parents/Caregivers Can Do:

Become familiar with the resources provided by the school for math learning.

Have regular check-ins with your learner about 1.) their current progress/struggles in math and 2.) what resources they are consistently utilizing.

What Educators Can Do:

Take a “lab” approach. See classrooms as a place to tinker and experiment. Encourage learners to test hypotheses they have about math and math learning. Invite learners to share their strategies and go-to resources. Facilitate discussions and cultivate collaboration as learners explore math together.

Become a curator. Explore math resources yourself. Watch YouTube videos and experiment with AI tools. Share these resources (and how they’ve been useful to you) with young people.

Attend to social networks. Each learner possesses knowledge and skills they can share with someone else. Each learner should also be able to “tap” into the resources of the community and get support from peers.

What Learners Can Do:

Become familiar with the resources provided by the school for math learning.

See technology as an assistant, not a crutch. It’s tempting to turn to AI to solve problems for you, or click through an e-learning platform without learning the content. Remind yourself that when you take shortcuts, you only cheat yourself.

Be willing to approach your peers for help, and be open to helping others. In a learner-led space, you are a learner and a teacher!

Challenge is Welcome

A third key mindset that we identified in the data was the ability for learners to engage with (and embrace!) challenging work. Instead of avoidance, procrastination, or taking a victim-mindset, these learners see the challenges that come with learning math as growth opportunities. Weaving through the concept of “challenging work,” we identified three overlapping themes: a focus on mastery, a deep feeling of agency, and a strong confidence to showcase competence.

Mastery Over Completion

One learner noted the best advice they got from an educator: “The best feedback I've ever gotten is ‘Mastery over completion.’ This…helped me want to learn things more deeply instead of just cheating my way through math.” This sentiment surfaced in a variety of interviews, with many learners saying their goal in math isn’t to get the right answer, but to understand the concept. “When I don’t understand something, I get the answer wrong on purpose,” one said. “Then Khan (the e-learning platform) will walk me through the problem step by step and I can see how to solve it.” This is a mindset shift for a lot of learners who come from math classrooms where priority is placed on getting the right answer and moving on to the next question (either in homework or on a standardized test).

My Way, My Pace

When asked about their favorite part of The Forest School’s approach to math, the majority of learners had the same answer: the freedom to go at their own pace. A close second was another familiar theme: the freedom to learn in a way that works best for them. For some learners, that means working through a textbook. For others, that looks like completing units on an e-learning platform. Participants in this study were quick to point out the ways they customized their approach to learning math. With this mindset, young people see themselves as active agents in the process, with the freedom to choose how and when they will practice their math skills.

I Can Show What I Know

We asked learners to give evidence that showcased their math mastery. The answers varied, with many participants citing dual enrollment credits, test scores, and progress on platforms. Another theme emerged in the conversations: the confidence to show what they know. “I can teach others how to do it,” one learner said. “I think that’s strong evidence.” This was a recurring theme in the data analysis. Math mastery was something that could be applied, not just a test score or abstract understanding of a concept. Learners felt confident that they could do math, and teach others to do it as well.

Why It Matters

In Phase Three of the Pathway of Self-Directed Learning learners take initiative (they set goals, make time, and get started) and in Phase Four, they persist in the face of challenges. The mindsets in this section (focus on mastery, sense of agency, confidence to show competencies) help learners push through challenging work.

What Can Be Done?

Many of these mindsets may seem dependent on the individual, but there are ways we can encourage and support learners as they develop these attitudes and beliefs. Below are some suggestions.

What Parents/Caregivers Can Do:

Growth mindset praise. Celebrate the process and the effort, not the product.

Don’t enable a “victim mindset.” When learners vent and express frustration, turn the conversation back to what they can do to overcome the obstacles in their way.

What Educators Can Do:

Support goal setting. Work alongside learners to create processes and protocols for setting math-based learning goals, reflecting deeply and often on progress, and pivoting as needed.

Give meaningful choices. What freedom do learners have in choosing how and when they learn math? How can these choices be encouraged, supported, and celebrated?

Design for application. How often are learners using their math to solve real problems? Embed math learning and practice across a variety of learning experiences.

Celebrate what you want to cultivate. Praise learners (publicly and privately) who are owning their math learning by setting goals, persevering through challenges, and being a resource to others.

What Learners Can Do:

Don’t take a “victim mindset.” Learning math can be challenging. It’s easy to get frustrated. Take a growth mindset, keep working, use your resources, and make progress. Over time, what was once challenging will become easier. More importantly, you’ve developed the skills and habits of learning how to teach yourself anything!

Seek mastery. The goal of learning math is to learn math, not to complete a course. Approach your learning with the mindset that you want to build your math knowledge and skills.

Practice teaching others. A great way to self-assess whether you understand a concept is to successfully explain it to other people.

Part 2: Strategies

In analyzing the data, here are the most useful strategies learners identified that help us answer the question “How do they learn math?”

Take Advantage of Resources

In an earlier section, we identified a key mindset of participants in this study: they recognized their resources. Here, in a move from mindset to strategy, we want to highlight how learners are utilizing their resources (a key role for educators and school leaders is providing helpful resources to learners).

Math Office Hours

At The Forest School: An Acton Academy, we have a Math Specialist that comes in for weekly office hours. Learners are able to utilize these office hours, bringing their questions and wonderings. The specialist operates Socratically (poses questions, recommends resources, prompts deeper inquiry), gently guiding the learners towards understanding. One hundred per cent of learners we surveyed reported making use of math office hours.

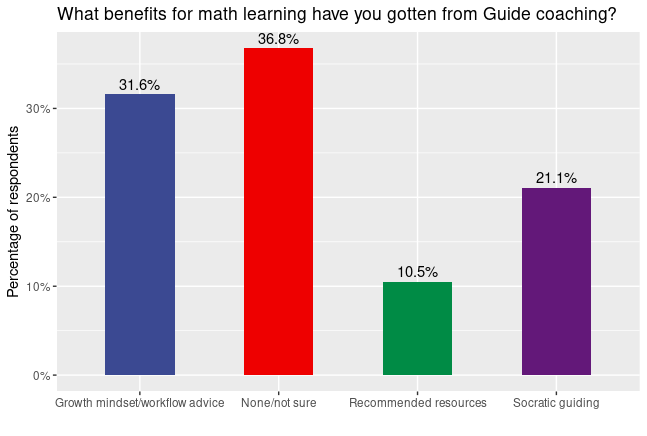

Math Labs

Math Lab is a signature learning experience that The Forest School: An Acton Academy offers weekly in our Upper Elementary (grades 4-5), Middle (grades 6-8) and High School (grades 9-12) Studios. 68% of participants indicated that they “always” or “often” attend Math Labs. 21% reported they “sometimes” attend.

E-Learning Platforms

Participants viewed their platforms as a resource, not just as “work to complete.” They’re familiar with the tools on the platforms. They know where to find videos, tutorials, and guides.

Digital Tools

When asked what happens when they get stuck, one high school learner responded: “If I still can't understand it…I'll find a video on YouTube. After that…I kind of restart the process over and find different resources and different apps that I could use that'll help me break it down…I might paste the problem in ChatGPT and have it break down the steps.” Participants largely saw digital resources (websites, apps, videos, and chatbots) as resources to utilize.

Peers

“I ask a friend.” That was a common refrain in the interviews. 72% of those surveyed said they turn to a peer when they get stuck on a problem. About a third of participants said they self-organize into study groups when working on math. A clear strategy for these learners is that they view math learning through a communal lens and don’t feel like they’re alone on their journey.

Why It Matters

When learners express a frustration in math learning, the first questions educators at The Forest School ask are “What have you tried? Who have you asked? Have you been taking advantage of Math Labs and Math Office Hours?” What we’ve learned from talking with learners who have demonstrated mastery in math is that they take full advantage of the supports available to them.

What Can Be Done?

There are a variety of ways to help young people take advantage of their resources. Below are some tips.

What Parents/Caregivers Can Do:

Become familiar with the math resources available to your learner.

Have regular check-ins with your learner about 1.) their current progress/struggles in math and 2.) what resources they are consistently utilizing.

Resist the urge to “rescue” learners. When they express frustration in learning math, discuss what resources they’ve used and which ones they may have overlooked.

What Educators and Parents/Caregivers Can Do

Make a list. With learners, create an exhaustive list of all the resources they have at their disposal when it comes to math learning. Post it prominently somewhere so it’s top of mind.

Refer to supports, Socratically. When learners express frustration over math learning, ask questions to probe their thinking. Ask them what they’ve tried, who they’ve talked to, and what resources they’ve explored.

Regularly “hold up a mirror” to learners, asking them to reflect on which resources they are using and which they aren’t taking advantage of.

Track the use of resources and update them accordingly (i.e., changing e-learning platforms or offering new supports).

Celebrate what you want to cultivate. Shout Out young people who are opting into learning experiences like Math Office Hours, self-organizing into study groups, and being a “go to” mentors to their peers.

Resist the urge to “rescue” learners. Using resources is a mindset before it becomes a strategy. Any “shortcuts” we offer young people deny them the process of building habits for mastering their math learning.

What Learners Can Do:

Become familiar with the resources provided by the school for math learning.

Take advantage of the resources available! Attend and engage with experiences like Math Labs. Seek out support in Math Office Hours.

Seek help from a peer.

Form a study group with peers working on the same material.

Be a mentor.

Use technology as a tool, not a shortcut.

Break it Down

Another theme that surfaced in the interviews and survey data was breaking down complex problems into simple steps. A variety of “process-oriented” strategies were discussed. The basic process was something like this: think, write it out, try, tinker, explore, and check.

Strong Math Fluency

“I try to do it in my head first,” said a middle school learner. “If I can’t figure it out, then I’ll write the problem out.” Participants showcased confidence in their mental math abilities, trusting that they could reason their way to solutions of basic problems.

Write It Out

Some learners gravitate toward white boards and dry erase markers. Others have notebooks. A key strategy was writing the problem down and identifying the steps in the process. By walking through a problem step by step, learners were able to identify when an error was a misapplication of a concept or a careless mistake.

Trial and Error

Another way of breaking a problem down: get it wrong on purpose. We saw this before in the mindset section (“mastery over completion”), but it also applies as a strategy. If learners are unsure of the steps to take in solving a problem, they get it wrong and the e-learning platform will walk them through the problem one step at a time.

Seek Another Perspective

If learners have already tried to tackle the problem on their learning platform and still can’t grasp how to break it down, they’ll turn to other resources. They’ll watch videos on YouTube. They’ll get assistance from an AI chatbot. They’ll ask a peer or take the question to Math Office Hours.

Check Your Work

Participants were also agile in knowing how to test a solution. They could check their work (on a white board or app) to confirm their understanding of a concept. This helped them identify errors in process or application.

Why It Matters

Learning math is a scaffolded process. As math concepts get more complex and the work increases in difficulty, young people can get overwhelmed at the scope of formulas and proofs. By gaining confidence in breaking down larger problems into smaller, more manageable pieces, learners stay motivated when faced with challenging work.

What Can Be Done?

There are ways to support learners as they develop these strategies. Below are some recommendations.

What Parents/Caregivers Can Do:

Praise the process, not the product. Give growth mindset praise to learners as they engage in the hard work of building fluency and mastering foundational skills in math.

When discussing math with learners, ask them about their process. What do they do when they’re learning a new concept?

What Educators Can Do:

Cultivate a culture of “process.” As learners move from lower to higher math, they have to shift from focusing on a “right answer” to a “sound process.” That shift can feel less rewarding (especially for those with strong math fluency) and more overwhelming.

Make learning visible. Encourage learners to write out the problems they're working on. Create spaces where learners can post problems, pose questions, and crowdsource solutions.

“How do you know?” In a world where it’s increasingly easy to paste a math problem into a chatbot or website and get an answer, shift the focus to having learners explain their process. At The Forest School: An Acton Academy and The Forest School Online, we’ve developed these learner-centered evaluation strategies.

What Learners Can Do:

Build math fluency! Practice and grow your skills in mental math, challenging yourself to quickly and accurately work through a variety of math operations.

Write out problems! Use a notebook or whiteboard to write down a problem and break it into steps.

Use trial and error. Don’t be afraid to try an approach and get a problem wrong. Learn from your mistakes.

Start with the videos on your e-learning platform. If you still are struggling to understand a concept, turn to other resources like YouTube or ask a peer.

Check your work. Test your solutions and seek deep understanding of the concept before you move on to the next topic.

Do Something…Anything

This bucket of strategies is all about taking action, breaking inertia, and doing something. When faced with a challenging task, it’s common to respond by doing nothing: waiting, procrastinating, seeking distractions, avoiding, etc. We learned from the participants in this study that just getting started is often the biggest barrier to overcome.

Set a Goal / Make a Plan

Action is tied to intention. Before there can be urgency, learners must see a compelling why to their math learning. We highlighted earlier in the “mindsets” section that participants in this study saw a clear relevance to their learning: either tied to present interests, connected to a desire to know things for the sake of knowing things, crucial to their career tracks, or necessary for college admissions. Once learners can have a “big picture view” of their learning journey, they’re able to make learning plans and set relevant goals. This goal-setting and plan-making is an actionable step that supports learners in making daily progress.

Make the Time

Tied to goal-setting, learners are making time in their schedules to work on math. 67% of participants reported they spend at least thirty minutes daily on math (we recommend that learners spend at least forty-five minutes daily on math). In the absence of a “math class” governed by a bell schedule and without a teacher taking attendance, these young people are making time to progress on their learning goals.

Make an Effort

Just try it out. That was the wisdom shared from a number of learners. “I see if I can do it,” said one. “I’ll try to figure it out in my head first,” said another. “I keep a journal,” reported a learner. “And I go back to review what I’ve already done.” Start your math time with intention, either reviewing previous material or trying something new. Take the first step and see how far you get.

Embrace the Pivot

Learners will hit a wall when exploring a new concept. They’ll get stuck, their strategies will falter (we previously conducted research on learner-centered strategies for overcoming barriers). Participants in this study talked about how they pivot. “I’ll take a break,” one said. “And try again when I’m fresh.” “I have to move,” said another. “Take a walk, get outside.” Others said they were quick to find other videos or tutorials. Many said they would take it to a peer. Instead of throwing up their hands in frustration, these learners had strategies for self-care, self-regulation, and resource-utilization.

Why It Matters

It’s tempting to put off or avoid challenging work. In order to support learners “persist” in a learning challenge, they must first take “initiative” (see again our Pathway of Self-Directed Learning). Moving from distraction to action is a combination of mindset shifts and habit building.

What Can Be Done?

There are ways we can encourage young people to get started on their work. Below are some recommendations.

What Parents/Caregivers Can Do:

Celebrate effort, growth, and good habits over performance.

When discussing math with a learner, ask them how much time they are devoting everyday to learning math.

Ask learners what their “plan” is for math learning.

What Educators Can Do:

Make the “why” explicit. Support learners in seeing the relevance in their math learning and help them make connections to their own interests and plans for the future.

Measure what matters. What goals do learners have for math learning? How much time are they making (daily, weekly) to meet those goals? This data can be tracked, shared, and celebrated.

Do some storytelling and resource-sharing around pivots. When have you had to pivot from one way of doing something to another? Crowdsource (with learners) a list of ways to “pivot” when learning math.

What Learners Can Do:

Make a plan. What math concepts do you need to master this school year? How will you make daily progress on achieving that plan?

Make the time. Spend at least 45 minutes on learning math, every day.

Don’t procrastinate! Get started. When you feel stuck, find a way to make a small step forward.

Learn to pivot! When you try something and it doesn’t work, find another approach.

Take a break when you need to.

LEARNER-RECOMMENDED IMPROVEMENTS

On the survey, we gave participants the option to suggest improvements the school could make to better support math learning. Here is what they said:

“Math application needs to be done more often. We aren't required to show what we are learning frequently, which makes us forget it.”

“More availability by the math guide.”

“Doing dual enrollment has helped me significantly, so I would say possibly requiring dual enrollment for basic math classes (such as college algebra).”

“I would like more group learning sessions where all people who are learning one math meet up and walk each other through a challenge.”

“Harder math lab questions or just more groups for people who would benefit from harder questions.”

“More options to show mastery, because tests don’t work for everyone.”

This feedback welcomes some "How might we" questions that we at Forest and other leaders and educators can consider. For example:

How might we incorporate more real-world math applications into our curriculum to ensure students regularly apply and retain what they learn?

How might we increase the availability and accessibility of math guides or specialists to provide consistent, individualized support?

How might we expand or promote dual enrollment opportunities, such as offering college algebra, to challenge students and better prepare them for advanced math?

How might we design into the schedule—or incentivize learners to design into their schedules—regular group learning sessions where learners can collaborate, share strategies, and work through challenges together?

How might we develop differentiated math lab activities that cater to varying levels of mastery, ensuring all students are appropriately challenged?

CONCLUSION

Here are the main learnings we took away from this study:

Successful math learning is a combination of MINDSETS and STRATEGIES

When young people take charge of their learning, there are things they must believe (mindsets) and things they must do (strategies). Our role as educators and parents/caregivers is to give learners practice, support, and freedom to develop their attitudes and actions toward math learning.

These (mindsets + strategies) are learnable

Anyone can learn how to shift their thinking and build their strategies. Too often, math and math learning is seen as a set of “fixed” traits—some people are “math people” and some aren’t. That’s not what we learned when we talked to young people. Many of them, in fact, didn’t see themselves as a “math person,” they had just developed the mindsets and strategies to learn what they needed to learn.

There isn’t one answer to the question, “How do they learn math?”

Learning is complex and varied. Each person has their own approach. What we noticed about participants in this study is that they could articulate their approach, including how they developed it, how it changed over time, and how they stay motivated when work gets challenging. There is no “silver bullet” to mastering math. Instead, young people find compelling reasons to learn, gather and utilize their resources, get started, and build habits to persevere when the challenges come.

Appendix

Survey Questions

Do you see a clear connection between learning math concepts and your own goals for your life (including attending college and/or pursuing a career)?

On a scale from 1 to 5, how would you rate your current mastery of math concepts? (Likert scale, very poor to very strong)

How often do you attend Math Labs? (Likert scale, never to always)

How often do you seek help from a fellow learner with math? (Likert scale, never to always)

How often do you gather in small study groups with other learners to work on math? (Likert scale, never to always)

How often do you use Math Office Hours? ((Likert scale, never to always)

Rank the math resources at The Forest School, with #1 being the one you find to be the most helpful:

Math Labs

Peer Mentor

Small Study Group

Math Office Hours

E-learning Platform (Math, Zearn, IXL)

YouTube tutorials

In addition to the resources in the previous question, do you have other resources you use consistently (flash cards, small white boards, etc.)? If yes, what are they?

How much time do you spend on math learning and practice every week?

0-1 hour

1-2 hours

2-3 hours

3-4 hours

4+ hours

How much time do you spend on math learning and practice every day?

0-30 minutes

30-60 minutes

1-2 hours

2+ hours

Outside of your math e-learning platform, how often do you use math-related skills (for example, analyzing graphs/charts and logical reasoning) in other signature learning experiences (Launches, Quest, Civilization, and Story Arts)?

0-1 time per week

1-2 times per week

2-3 times per week

3-4 times per week

4+ times per week

What have you appreciated the most about learning math at The Forest School?

What has frustrated you the most about learning math at The Forest School?

What one change would you make to improve the way math is learned at The Forest School?

Interview Questions

How would you describe your current mastery of math?

What evidence makes you think/believe that?

How do you know your level of math learning?

How has your approach to understanding your level of math learning changed over time?

What resources provided by The Forest School have been the most helpful to you in learning math?

What resources have you found on your own that have been the most helpful to you in learning math?

What is one tool or resource you wish you had for learning math?

Walk me through your own approach to learning math. If you encounter something new and aren’t sure how to do it, what do you do next?

What’s the culture of math learning like in your Studio? Are there mentors that help other people out? Do learners ever form study groups?

Describe a time when you felt successful learning math at The Forest School. What made it successful?

How do you stay motivated to work on challenging math problems?